I’ve been learning about biological ageing over the last few months for a project. There’s so much to take in just on the basics, let alone the new research coming out. To help myself make sense of it, I’ve decided to write up my notes on various papers, starting with The Hallmarks of Aging.

Sources

The primary sources for this post are:

The Hallmarks of Aging by López-Otín, Carlos et al, published in Cell in 2013.

Week 7 of Epigenetic Control of Gene Expression, a course I’ve mentioned in a post on learning genetics and epigenetics.

There are full references and other links at the end of this post.

I’m a software/AI person trying to understand the language and ideas in ageing. If you spot places where I’ve misunderstood, I lack a clue, or you have suggestions, do get in touch. Twitter or LinkedIn are probably the easiest ways to grab me.

What is ageing?

Ageing is a progressive decline in how we function. There are other aspects of ageing in society, but I’m thinking only of the biological ageing here. (If you’re interested in a broader treatment, take a look at the Sep/Oct 2019 issue of MIT Technology Review, which includes articles on product design and attitudes to ageing.)

Where does this decline come from? In general, it is:

the accumulation of damage; and

over-activity of some processes leading to disease (which I’ve discussed in more detail in a post on quasi-programs).

Why does it matter?

This age-based deterioration is the leading risk factor for many diseases, including diabetes, cardiovascular, and neurodegenerative problems. Some of these conditions have no long term treatment, let alone cure.

And yet some people can live without these problems. They have both a long healthspan and lifespan. We now know genetics and biochemistry control ageing (more on that later). So the question is: can anyone potentially live without having to experience long periods with one or more of these diseases? If so, what kinds of lifestyles and treatments might give us that?

Terminology

There are a few common words and phrases that are worth knowing before diving in any deeper:

- Ageing vs Aging: The UK vs US spelling.

- Longevity: “increased longevity” means living for longer.

- Healthspan is how long you live without disease.

- Chronological age is… your age. How long you’ve been alive for.

- Biological age: if you are ageing faster (or more slowly), your biological age would be above (or below) your chronological age. There’s no definitive way to measure this. Various models exist that combine multiple factors (lung capacity, cholesterol, skin elasticity, and so on) into a single value, but the ideal would be to find a biomarker for ageing.

- A biomarker for ageing. This would be a standard, validated, test from, say, blood or saliva, which would give a biological age. This is important because it would make it possible to measure the effects of interventions.

- Senescence: the precise term for biological ageing.

- Tissue, a collection of cells with similar function or structure. I might say “heart tissue”, “lung tissue”, and so on.

- Signalling Pathways. I don’t have a grasp on the biological terms of “circuit” and “programs”, but I think I get “signalling pathways” now. These describe the influence of, say, proteins, and how they inhibit or stimulate other proteins. I’ll show one later in this post.

Hallmarks of ageing

In 2013, The Hallmarks of Aging proposed nine common features of ageing. To be included a hallmark had to:

be a normal part of development (as opposed to the result of being hit on the head or something external);

when increased, ageing speeds up; and

ideally, when a hallmark is reduced or prevented, ageing is slowed.

I’ll list out the nine hallmarks below, but I think it helps to know they fall into one of three groups:

causes of damage;

response to damage; and

causes of the phenotype (appearance) of ageing.

Let’s look at the nine hallmarks by group.

The causes of damage

Bear in mind that cause and correction aren’t fully worked out. But the items listed below are hallmarks because they have shown increasing them speeds up ageing (and in some cases the reverse has been shown).

Genetic: that is, DNA damage we accumulate, or specific premature ageing diseases. The genome has lots of repair mechanisms but isn’t perfect. Replication mistake or external factors (such as smoking) lead to mutations. This is a broad category and interacts with many of the other hallmarks. Cancer is the headline consequence.

Epigenetic changes. Epigenetic marks are chemical additions to your genome which changes how your genes are expressed (if they are on, or off, in a particular tissue, for example). “Epigenetic drift” is the name for the stochastic errors that naturally occur over time and between individuals. The accumulation of these changes is associated with ageing. We’ll see some a specific example later. There’s also an interaction with the genome: some epigenetic changes may lead to genome instability, which may impact epigenetic marks, which may lead to more genome instability, and so on.

Telomere shortening. Telomeres are compact regions of DNA at the start and end of the chromosomes. They prevent the DNA repair machinery from treating the ends as a break in a chromosome to be repaired. When a cell divides, and DNA is copied, but not to the end. The telomeres become shorter over time, and eventually, the cell shuts down.

Loss of proteostasis, which means not being able to generate and remove proteins at the right rate, or correctly fold proteins. Folding problems are associated with Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s (as well as cataracts).

Responses to damage

This second group of hallmarks are beneficial in low doses (offering some kind of protection or repair), and bad when high (which happens during ageing).

Deregulated nutrient sensing. One idea here is that you survive for longer if you have lower rates of cell growth and metabolism (giving lower rates of damage). In other words, decreased nutrient sensing increases longevity. Although this happens as we age, there’s strong evidence (not just in mice) that explicit dietary restriction increases lifespan and healthspan.

Mitochondrial dysfunction. The “powerhouse of the cells” lose efficiency over time. Terrible news, but surprisingly (to me) limited “mitochondrial poisoning” increases efficiency. This is an example of how a small amount of stress can help as our bodies compensate (but only up to a point).

Cell senescence is a situation where cells no longer divide and become inactive. It’s a protective mechanism (against cancer) in the young, but an increasing problem over time.

Causes of the appearance of ageing

The final two hallmarks are the result of the other seven we’ve seen:

Stem cell exhaustion. Cuts heal when epidermal stem cells divide to create new skin cells. When exhausted, they don’t divide as fast, meaning cuts take longer to heal. At an extreme, they don’t heal at all. That’s an example of stem cell exhaustion, but it applies to the immune system and other tissues. It is a “consequence of multiple types of aging-associated damages and likely constitutes one of the ultimate culprits of tissue and organismal aging.” (The Hallmarks of Aging, p. 1206).

Altered intercellular communication. In addition to changes at the cell level, there are changes in the interaction between cells. This appears to cover a wide area: reduce immune response, increased inflammation, diabetes, atherosclerosis, muscle weakness, and generally a whole lot of undesirable changes.

In summary:

“The primary hallmarks could be the initiating triggers whose damaging consequences progressively accumulate with time. The antagonistic hallmarks, being in principle beneficial, become progressively negative in a process that is partly promoted or accelerated by the primary hallmarks. Finally, the integrative hallmarks arise when the accumulated damage caused by the primary and antagonistic hallmarks cannot be compensated by tissue homeostatic mechanisms. Because the hallmarks co-occur during aging and are interconnected, understanding their exact causal network is an exciting challenge for future work” (The Hallmarks of Aging, p. 1209).

Example suggestions for treatments

There’s plenty of evidence to accompany the hallmarks, and that evidence suggests interventions to reduce ageing. Here are a couple of them.

SIRT6

There are a family of proteins called sirtuins, one of which is SIRT6. SIRT6 is involved in laying down histone acetylation (a sort of epigenetic change), and this reduces with age.

In mice, reduced SIRT6 leads to defective DNA repair, and accelerates ageing. Increased SIRT6 expression increases lifespan. It may also play a role in reducing inflammation.

You can see why there’s a search for a drug that can have this effect, via this mechanism, without causing side effects.

mTOR

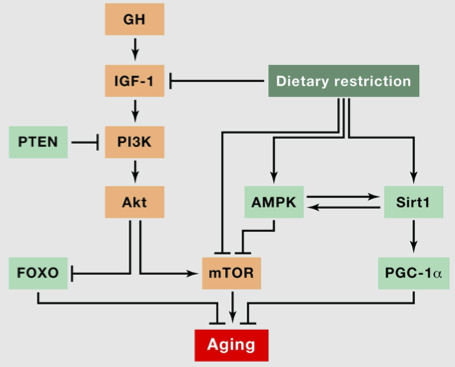

Take a look at the signalling pathway relating ageing and dietary restriction (this is figure 4A from The Hallmarks of Aging, p. 1202):

The diagram is mapping out the nutrient sensing hallmark. We can see that mTOR, an enzyme, has a role in increasing ageing, while dietary restriction inhibits mTOR. This is one way in which to understand how nutrient sensing impacts ageing.

This suggests targeting mTOR may have benefits for ageing. Rapamycin, a compound that inhibits mTOR, is being investigated for this.

Summary

We’ve seen:

a little bit of background on ageing;

the nine hallmarks of ageing, where a hallmark is a natural part of development, and increasing or decreasing the hallmark effects ageing; and

a couple of examples of how the mechanisms and evidence play into those hallmarks to suggest treatment.

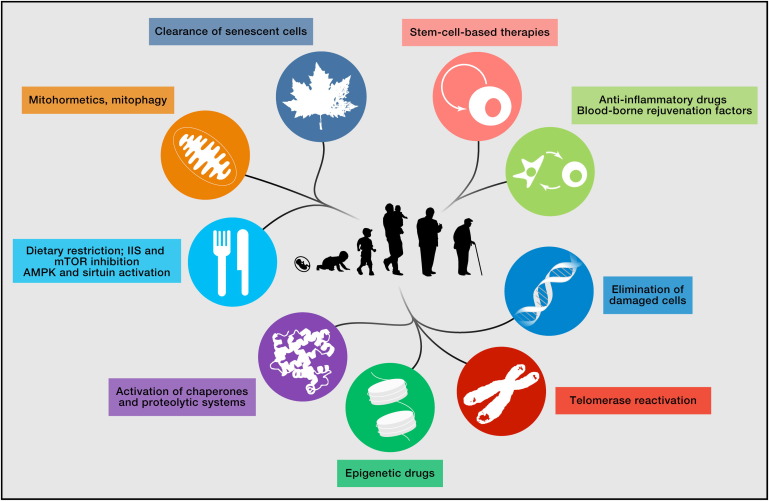

The paper is important because it gives a framework for thinking about ageing and how we might improve healthspan. Even if you don’t read the paper, have a look at figure 7. It shows possible treatments (based on experience with mice).

If you’re interested in learning more, scroll down through the reading below. Don’t miss the short video at the bottom.

Further reading

Academic literature

- López-Otín, Carlos et al (2013) The Hallmarks of Aging. Cell, Volume 153, Issue 6, 1194 - 1217, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039

- Partridge L, Deelen J, Slagboom PE. Facing up to the global challenges of ageing. Nature. 2018;561(7721):45–56. doi:10.1038/s41586-018-0457-8

Popular science and news

- The Mindscape podcast from Oct 2018 features a conversation with Coleen Murphy on Aging, Biology, and the Future. 1hr.

- Chapter 13 of The Epigenetic Revolution is on ageing.

- MIT Technology Review, Sep/Oct 2019 issue is on longevity, covering biology, medicine, society’s perceptions of ageing, and product design.

- How medical science hopes to slow down ageing, The Economist, 15 Aug 2016. This is a short explainer on the discoveries driving ageing research.

- Scientists harness AI to reverse ageing in billion-dollar industry, The Guardian, 21 Dec 2019. This item is on the recent focus and investment in the race “to find proven ways to help people live longer, healthier lives”.

- A fantastic 10-minute video on Extending Human Lifespan by Kristen Fortney. It covers the ideas, history, and interventions relating to extending lifespan (thank you Suran for this link).