I’ve been flummoxed by some basic statistics questions recently. I’m not alone in this, as it’s a common one for students and 17th-century gamblers. I’m taking this chance to note this down for when I make the same mistakes again.

The problem

I was reading the (now out of print) Evolutionary Genetics text, and tackling question 2a at the end of chapter 1. My intuition was wrong.

The question was around the chances of generating a 19 character phrase from random letters. Here’s the question:

For simplicity, ignore spaces, and let the ‘correct’ 19-letter message be ‘METHINKSITISAWEASEL’. Start with a single 19-letter message, in which each letter is randomly chosen from the 26 letters. What is the probability that at least one of the 19 letters is correct […]?

In other words, you have a random 19 letter phrase. What are the chances that at least one of those 19 letters matches up to the corresponding letter in ‘METHINKSITISAWEASEL’?

Feel free to pause and figure it out.

My intuition is wrong

My thinking was: OK, the chances of getting a letter right is 1/26. But I have sort of 19 goes at this. So the answer is 19 x 1/26 (or 19/26, which is 0.73). This is wrong by a wide margin.

My way to understand this is by drawing a simplified table of all possibilities, which I’ll reproduce in a moment. And I’ll also show the answer given in the textbook. But before that, it’s fun to note that a similar problem appears in The Art of Statistics.

There we learn that Antoine Gombaud (1607-1684) tried to calculate the odds of winning in two gambling games and got it wrong for much the same reason as I have. A footnote David Spiegelhalter comments: “these are still common errors made by students”, and he gave an excellent suggestion to see how my reasoning must be wrong. Imagine if, rather than 19 letters, we have 52 letters. Then, according to me, the chance of having one letter correct would be 52/26, which is 2. (Also: thanks to Miles who pointed out the same sanity check).

Gombaud’s error led to the foundation of a theory of probability. Mine meant I had to spend a lot more time to get on to chapter 2.

Visualising my error (the long way)

To work out the right answer, I looked at a more straightforward problem that I could draw out by hand. I cut down the number of letters and the length of the word.

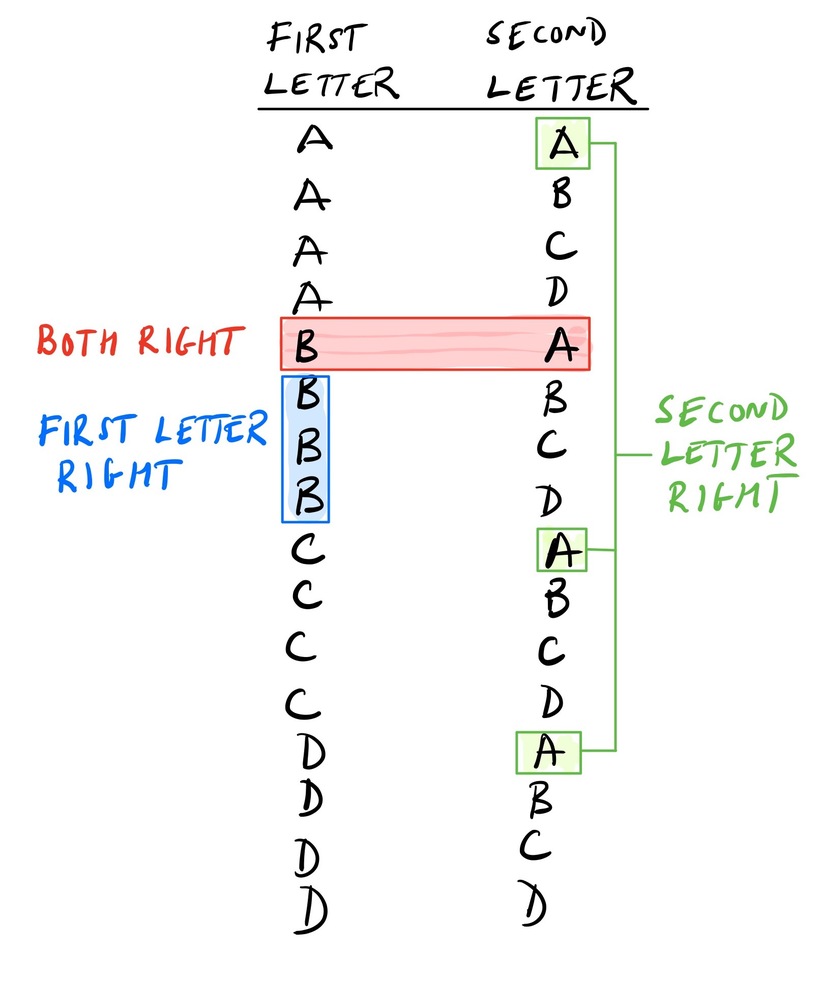

Image trying to guess the word “BA” from a randomly generated two-letter word. And let’s cut the alphabet down to just the four letters, A-D. What’s the chance of guessing at least one letter right?

My incorrect reasoning would say 2 * 1/4 = 0.5, but I can see this is wrong by drawing the problem space:

I can now see the chance of getting at least one letter right is:

- three rows where the first letter is right;

- three where the second is right; and

- one where they are both right.

That’s 7 rows out of 16, or 0.4375. That shows my intuition (0.5) is an over-estimate because I’m double counting the row where the letters are both correct.

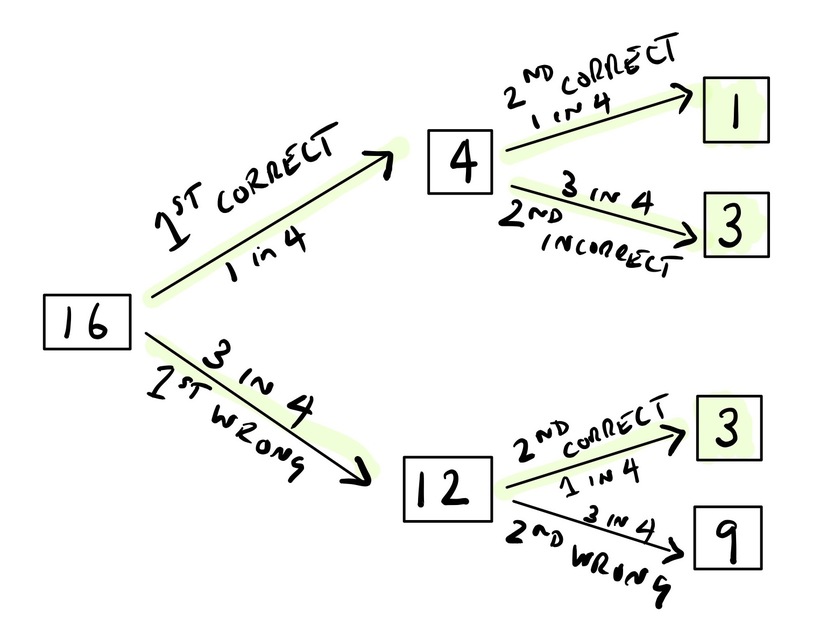

The Art of Statistics showed me an excellent way to visualise these kinds of problems. Think about the number of choices I have at the start, and the decisions I need to make:

The above is an expected frequency tree. We have 16 rows, and I care about the case where the first letter is right (1/4 chance) or wrong (3/4 chance). That splits the 16 rows into two sections. Then for each section, we can see what happens if the second letter is right or wrong.

In the end, that highlights three paths of interest: both letters correct, just the first correct, or just the second correct. That’s also 7 out of 16.

Update June 2021: This is all the “sum rule” in probability. That is, for this short example of just two letters from four is:

P(A) or P(B) = P(A) + P(B) - P(A, B)

…which is 0.4375 for two 1/4 chances.

The right answer (the short way)

What I need to compute is more along the lines of: (first letter and not second) or (first and second) or (second and not first). That works, but the textbook answer is much clearer.

For the original 10-letter problem, it goes like this:

- P(all 19 letters wrong) = (25/26)^19.

- So, P(at least one letter correct) = 1 - P(all 19 letters wrong).

The chance of getting at least one right is 1 minus the chance of not any right. It’s a common trick. Apparently.

For the original (19 letters, full alphabet problem) that’s 1 - (25/26^19) or 0.5254.

For the simplified (“BA”) problem it works, and we get the right answer too: 1 - (3/4 * 3/4), which is 0.4375.

Summary

I have learned that:

- I need to think in terms of frequencies. How many rows are there, how many are selected by the question I’m asking?

- I should ask if there’s an inverse (1 minus something) question that’s the same, but easier to answer?

- Drawing frequency trees or similar diagrams helps me check my working.

- By tripping me up so easily, Evolutionary Genetics is a great teacher.

And I am heartened by the words of David Spiegelhalter:

Even after my decades as a statistician, when asked a basic school question using probability, I have to go away, sit in silence with a pen and paper, try it a few different ways, and finally announce what I hope is the correct answer.